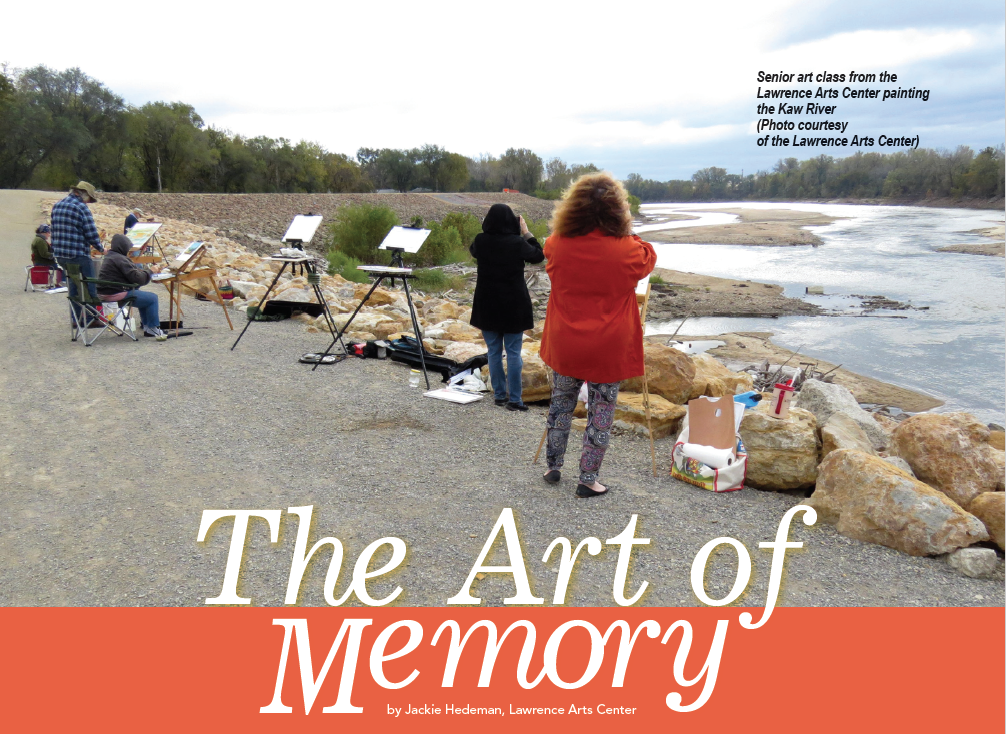

The Art of Memory

| 2018 Q2 | story by Jackie Hedeman | photos courtesy of the Lawrence Arts Center

More than once in my adult life, I have spent long minutes staring at my bedroom ceiling in the middle of the night, my brain looping a certain refrain: “Pink monkeys in Nebraska flip red, funky cars. Others retain permanently mushed pink faces.” This charming chant was a mnemonic device developed in an elementary school math class, a means of remembering an order of operations more elaborate than PEMDAS. I have long since forgotten what I was supposed to remember, though I obviously remembered it long enough to pass fifth-grade math. The chant remains in my brain, however, and with it the memory of jumping up and down in place with my classmates Amelia and Jonathon, and the ensuing argument about whether it was supposed to be “faces” or “faucets,” or even “facets.”

(Jonathon, if you’re reading, it was faces.)

The brain is a mysterious, undisciplined thing. Its capacity—or its incapacity—for memory has long been a fascination for scholars and researchers, and schoolchildren trying to get through math class. In order to remember, we make lists. We come up with songs and mnemonics. We tell our friends to remind us. We try all kinds of workarounds, most of which rely on assigning patterns and systems where, before, there was chaos.

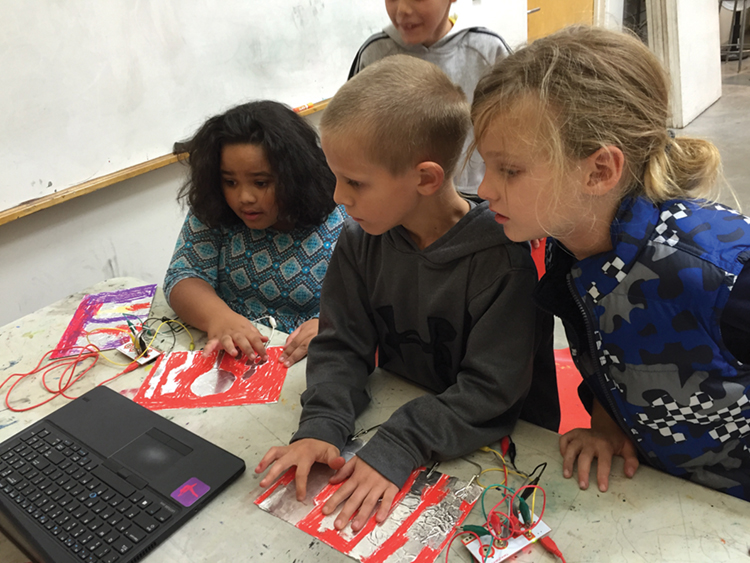

“Ars memoriae,” or the art of memory, has existed as a defined concept since approximately 500 BCE. A couple centuries later, Aristotle wrote extensively on images as memory aids. He posited that without an image in the mind’s eye representing a concept; understanding of that concept would remain elusive. Unsurprisingly, Aristotle was onto something. The notion of building systems of recollection around artistic practices fueled everything from early-Christian meditation to modern-day STEAM learning. STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art and math) differentiates itself from STEM through the use of artistic practices to underline, illustrate and complement science, technology, engineering and math principles. Integrating the arts into scientific study improves retention. This theory is borne out in an article in the “International Mind, Brain and Education Society” journal entitled “Why Arts Integration Improves Long‐Term Retention of Content.” Arts integration, the authors explain, takes advantage of how the brain encodes long-term memories. It’s not quite Proust’s “madeleine” we’re talking about here: Seeing a swath of color is not going to bring back knowledge of DNA sequencing. But sketching out a DNA sequence, or writing a DNA-inspired poem, builds associations and interest absent from rote memorization.

Schoolchildren are not the only people concerned with retaining memory. An April 2015 study published in “Neurology” journal followed 256 participants aged 85 and older. After four years had passed, 121 participants had experienced a decrease in cognitive abilities. However, participants who engaged in art, craft or social activities in mid- and late life were less likely to exhibit mild cognitive impairment. This may sound familiar. Many of us know people who attribute their longevity or sharpness to keeping busy, to getting or staying involved. Folk wisdom and science are in agreement at a time when taking such advice to heart is more important than ever. Internationally, the fastest-growing group consists of those 85 and older. Meanwhile, rates of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease are on the rise. Alzheimer’s Association statistics indicate that, in 2018, one in three seniors will die with Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia. Between 2000 and 2015, deaths from heart disease decreased by 11%, while deaths from Alzheimer’s increased by 123%.

The causes of Alzheimer’s are complex and interactive; a cure or even a mitigation will be equally complex. Nonetheless, studies have shown that practicing the arts throughout life is of concrete benefit to the brain. Professor emeritus Mark Posner, University of Oregon department of psychology, reaches a conclusion in his article “How Arts Training Improves Attention and Cognition.” He writes, “From our perspective, it is increasingly clear that with enough focused attention, training in the arts likely yields cognitive benefits that go beyond ‘art for art’s sake.’ Or, to put it another way, the art form that you truly love to learn may also lead to improvements in other brain functions.”

Professor Posner’s reasoning is supported by science, but its logic is ancient. In the “Rhetorica ad Herennium,” a book on rhetoric sometimes attributed to Cicero, the author suggests setting up “images of a kind that can adhere longest in memory.” They should have “exceptional beauty or singular ugliness.” They should be “striking,” “comedic,” ornamented. They should, in other words, have something in common with “Pink monkeys in Nebraska … ”

When it comes to memory, art is not merely a brainteaser, a tool of retention. Art can serve as a receptacle of memory, preserving stories and sentiments long after the brain has ceased to house them. We find these stories in memoirs, in music and film, on canvas. We can see them evoked in dance or with clay. Art admits the messiness of memory, the impossibility of the brain. Experiencing it, we can find solidarity and begin to build community.